Electric vehicles are taking over—and probably sooner than most realize.

California’s electric vehicle mandate, which passed in late August, will see the state halt gas-powered vehicle sales by 2035. Other states are expected to follow suit, with Washington, Massachusetts, Oregon, Vermont, and New York among the most likely.

These would be just the latest in a steady stream of legislation aimed at incentivizing EV production and adoption. Earlier this summer, the Inflation Reduction Act established valuable tax credits for EV buyers. And before that, it was the bipartisan infrastructure act and the FAST Act, taking aim at the inadequate charging network on American roads.

It’s not just coming from the top, either. Both business and consumer attitudes are changing, too. In the next two years, more than 50 new EV models will hit lots, according to Caryatid Consulting. And by 2040, a whopping 18 car manufacturers say they’ll be fully electric.

“There are a lot of people who believe that it’s impossible to eliminate combustion sales and that EVs are a fad,” says Scott Wise, co-founder of Refuel Electric Vehicle Solutions (REVS). “But these companies are putting billions and billions and billions of dollars into converting their manufacturing plants and to develop new battery technology. It’s just kind of hard to bet against.”

Wise, in fact, is doing the opposite. He left his 30-year career in real estate development to help other multi-family professionals prepare for the EV revolution.

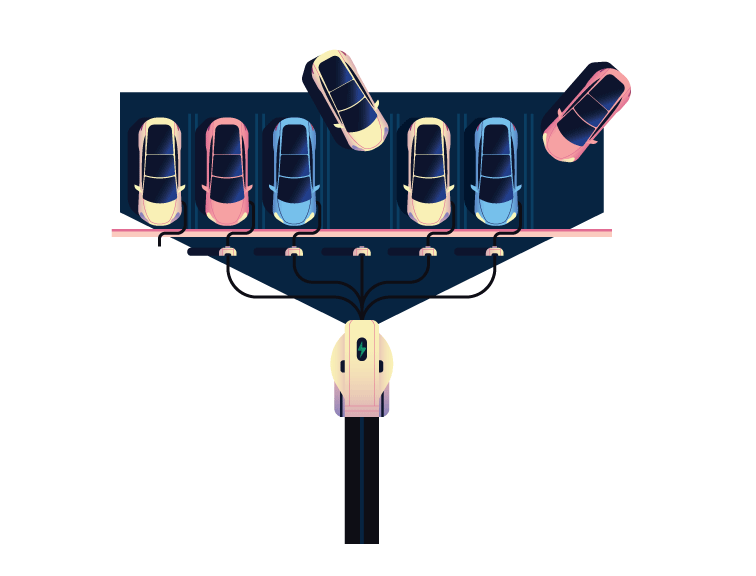

As he explains, “Multifamily parking lots, they need to be the fueling stations of the future. If multifamily doesn’t start defending against it, you’re going to be obsolete.”

Aldo Crusher

Getting in Early

The years 2035 and 2040 probably feel far away to most, but in the multifamily world they’re only a handful of renters down the road.

“Multifamily needs to defend against and capitalize on the impact that EV adoption is going to have on properties and portfolios over time,” Wise says. “It’s not

inconceivable that by 2030 you could have 25% of your vehicles on-site being EVs. In a typical 300-unit apartment complex, that’s 80 or 90 EVs. And then 10 years later, you could be at 90%.”

He’s right: 56% of consumers say the next car they buy will be either electric or hybrid-electric. For these drivers, having access to home chargers will be critical. In fact, according to the Department of Energy, 80% of all EV charging occurs at home.

There are also tax incentives to consider. The Inflation Reduction Act offers a $2,500 to $7,500 tax credit to consumers who purchase certain electric vehicles.

As Hemal Doshi, CEO of Universal EV Chargers, explains. “It’s expected that this incentive will result in rapid adoption of EVs across all price points.”

For multifamily properties, that shift will mean a drastic change in renter requirements over the next decade. And while some developments have already taken steps to prepare—or at least laid the foundation for future EV use—there’s still a long way to go to meet projected demand.

“There’s something like 1,700 apartment properties in the country now that have electric vehicle charging stations, and that number since 2013 has quadrupled,” says Ben Harrold, manager of public policy for the National Apartment Association. “We’re seeing this exponential growth of EV stations becoming much more present and much more important to both residents of apartment communities and their owners and operators.”

Burkentine Real Estate Group is one development company taking EV charging seriously. The company has 700 units under construction this year—a mix of apartments and townhomes scattered throughout Pennsylvania—and all of them will receive either garage EV chargers or have access to dedicated EV charging spaces in the community.

“Electric vehicles are going to be here regardless, and there’ll be a massive conversion of vehicles over time,” says Mike Burkentine, co-owner of the company. “Some people ask me, ‘Why would you spend the money? It’s not here yet.’ Well, if you think about the amount of money that it’s going to cost to tear up and actually put the infrastructure in, it’s cheaper for us to put them in now than it is to retrofit and do it later.”

The Time is Now

For those that don’t have EV chargers just yet—or who are putting the decision off, waiting for more proof of concept—experts say it’s time for a change of heart.

As Burkentine mentions, retrofitting a property with EV chargers (and the infrastructure to support them) is much more challenging and costly than doing it from the start.

By the Numbers

52%

of new U.S. vehicle sales are expected to be electric (excluding hybrids) by 2030

37

electric-hybrid vehicle models are currently available in the U.S.

19

all-electric vehicle models are currently available in the U.S.

59

new electric vehicles are being released in the next two years

18

major car manufacturers will go all-electric by 2040 (most by 2030)

27%

of all new EV coming to market in the next 10 years will cost $45,000 or less

60%

is how much EV registrations jumped in the first quarter of 2022

Sources: Courtesy Caryatid Consulting, Bloomberg New Energy Finance, Edison Electric Institute, U.S.Department of Energy, Experian, and the Inflation Reduction Act

“It’s more economical to install EV chargers in new buildings,” says Karen Cusmano, senior vice president and head of sustainability and ESG at Veris Residential, which has committed to installing chargers at all of its properties by 2030. “You get economies of scale if a contractor is also fulfilling other infrastructure needs for the property, plus you avoid disrupting residents’ daily activities.”

Additionally, the budgeting, analysis, and planning for an EV install can be weighty—so getting started well ahead of major demand will be vital.

In many cases, developers need to work with local utility providers or the city to ensure the property has adequate power to support EV charging—both initially and as need expands later on.

“This particular amenity requires heavy infrastructure,” Burkentine says. “You have to really think about what your power loads are and what your design is going to be.”

Finally, there’s overall marketability to consider, too. While EV stations can certainly make a property more attractive to EV-driving tenants, they also increasingly carry weight with investors—particularly those with environmental goals in mind.

“Installing stations isn’t just about serving the residents,” says Sue Vickery, a multifamily development consultant with Caryatid Consulting. “Most big investors have ESG requirements that will favor investment in properties who meet their guidelines.”

Paying for EV

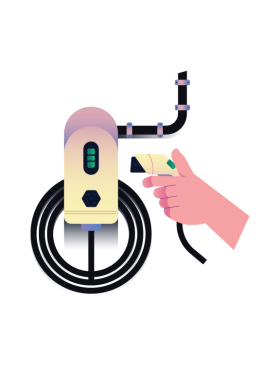

For many developers and owners, the cost of EV stations is enough to cause apprehension. On their own, charging stations can cost anywhere from a few thousand to upward of $10,000, depending on the type of charger purchased.

And that’s just the charger itself. There are also the costs of installation and setting up the infrastructure, which includes trenching, laying conduit, installing wiring, and preparing the site and utilities. These costs vary widely but can easily cost $100,000 or more, particularly for a retrofit.

Fortunately, most developers can start small, minimizing their costs with just a handful of spaces.

“To properly future-proof a property, I’d recommend enough stations initially to serve 10% of parking spaces—or at least one dual charger per garage level,” Vickery says. “What’s even more important, however, is ensuring conduit is laid to enable future expansion and to ensure the transformers on the property are sufficient to handle the current and expanded energy need.”

Owners generally have the option to lease their units and do a revenue share with the operator or purchase the stations and pass on some of those costs to renters, often with rental fees or usage charges. Though some choose to offer charging as a community amenity (with the costs borne by the property), Wise cautions about adopting this as a long-term approach.

“If you’ve got six Teslas on site, and they’re charging three times a month, you’re letting about $3,500 a year go out the door,” Wise says. “But what happens when you keep it on the house meter, you get to 2030, and now you’ve got 75 EVs on the property. It’s unsustainable.”

There are also countless incentives and rebates that companies can utilize to offset the costs of EV chargers. Some are offered through municipalities, while others come from utility providers. In Pennsylvania, for example, the Department of Environmental Protection reimburses multifamily owners for up to $3,500 per port or 50% of the total project costs. Massachusetts has a similar program, offering up to $50,000 per street address.

Various tax incentives—like the Alternative Fuel Vehicle Refueling Property Credit—can help, too. This one offers a tax credit worth 30% of the project cost, as long as the property is in a low-income community or a “not urban” area. These could be an option for affordable housing developments looking to begin EV adoption as well.

While this might not seem like an important priority for lower-income areas at the moment—particularly with EVs claiming an average $66,000 price tag—that will change over the coming years. In fact, 27% of EVs coming to market in the next two years will cost less than $45,000. Additionally, a robust used EV market could also be in place soon, making EVs much more accessible to budget-conscious buyers.

When coupled with the various state requirements that are expected for EV-only sales, it will likely necessitate chargers in every community—no matter the average income.

“Over the next two to three years, the used EV market will expand into even more economically diverse communities,” says Jeff Hutchins, president and chief technology officer at EOS Linx, an EV charging company. “EV charging infrastructure will become important everywhere.”

Aldo Crusher

Jumping on the EV Bandwagon

Planning ahead—particularly when it comes to finances—is paramount if owners hope to offer EV charging capabilities, even years down the line.

“The biggest obstacle that we’re seeing is people aren’t putting anything in their annual budgets,” Wise says. “If you’re not getting dollars allocated in your budgets today, then you’re probably not going to be able to do anything EV-related for the next year.”

Being proactive about the site’s power and utilities is important, too.

“The first thing you need to do is have a detailed report done,” Wise says. “We need to go out there, look at the breaker panels, look at your transformer, and see where you might have any extra power.”

According to Wise, REVS recently had a client whose site did not get enough power to support EV charging. They had to work with the utility company to get local transformers upgraded before construction could begin.

Burkentine says this process can often take quite a while—particularly if you’re dealing with smaller municipalities.

“It’s very interesting to be in these conversations, because you’ll have the electric plant manager, and they’re like, ‘We’re not exactly sure how we’re going to design this,’” Burkentine says. “It’s almost like you’re pioneering the way of the future within America.”

You’ll also need to zero in on where to place your stations (a central area by the clubhouse or scattered throughout the community) and decide how you’ll secure and operate the machines (rent versus own). There are also accessibility concerns, and you’ll need a plan for monetizing and managing the stations, too.

“The real challenges come after the chargers are installed,” Vickery says. “Management needs to develop policies and procedures around reserving spaces and monitoring use, charge backs, and/or revenue opportunities; maintaining the chargers; and monitoring legislation that may impact hardware or usage requirements.”

If it all sounds like a big undertaking, it’s because it is. But it’s one experts say is necessary if you want to future-proof your business and remain relevant for years to come.

As Cusmano puts it, “Whatever you do now should be forward-thinking. Prepare for expansion, because this world is changing.”