The primary implication is on valuations. It’s no secret that vulture funds have been amassing war chests since 2007. “It artificially buoys the market because there’s no product [being sold],” says David Lynd, chief operating officer of San Antonio, Texas-based The Lynd Co. “There’s been all of this money raised to take advantage of the distress and buy assets at true values, and none of it is coming to market. As a result, you’re getting artificially low cap rates, and values are higher for things that do come to market.”

Cash Strapped

Owners who avoid cap ex investment risk having a special servicer step in.

When The Canyons & Montelena at The Canyons in Phoenix was handed to a property manager in July 2009, the 600-unit property didn’t look like a five-year-old project. The previous owner had pulled appliances, plumbing, and even toilet seats from 69 of the units to keep the make-ready units online. As a result, the property was only 70 percent occupied.

Despite this, property managers managed to turn the property around—The Canyons is now 90 percent occupied.

Unfortunately, this is more the exception than the rule when distressed CMBS deals go into receivership. The problems start when the owners seek extra cash by either cannibalizing from other units or letting things go altogether. “The minute the owner becomes absentee, that’s the end of it,” says David Lynd, COO of San Antonio, Texas-based The Lynd Co. “They won’t continue to put money in a deal that they’ll get zero for.”

This often signals the beginning of the end. “The property starts looking tired,” says Stephen Roger, managing director of Capital Transactions for the Affordable Housing Group of New York-based Centerline Capital Group. “They see the property every day, [so] they don’t notice the deterioration. All of a sudden, they’re digging deeper and deeper for less and less qualified tenants.”

That can give servicers an opportunity to reclaim the property. “If we see that the current ownership is wasting the asset and not properly maintaining it, we’ll put a receiver on it,” says Michael Carp, head of Horsham, Pa.-based Berkadia Commercial Mortgage’s asset management and special servicing business. “We don’t want deterioration.”

If they decide to spend the money, though, one executive who manages for servicers says they will come through and make the necessary fixes. The problem is the logjam of properties. “The special servicers have so many assets to deal with, the focus is hard,” says one property manager who did not want to be identified in this story.

And others don’t think the servicers are investing to improve property values; they’re focused instead on pushing fundamentals. “[The servicers] bring in a good third-party manager but won’t spend cap ex dollars like they should,” says Mark Johnson, vice president of multifamily investment sales at the Multifamily Advisory Group of Colliers International, a Seattle-based commercial real estate services firm. “They’re not going through and putting in new roofs and redoing the interior package to raise value. They spend the time getting it as close to market as they can.”

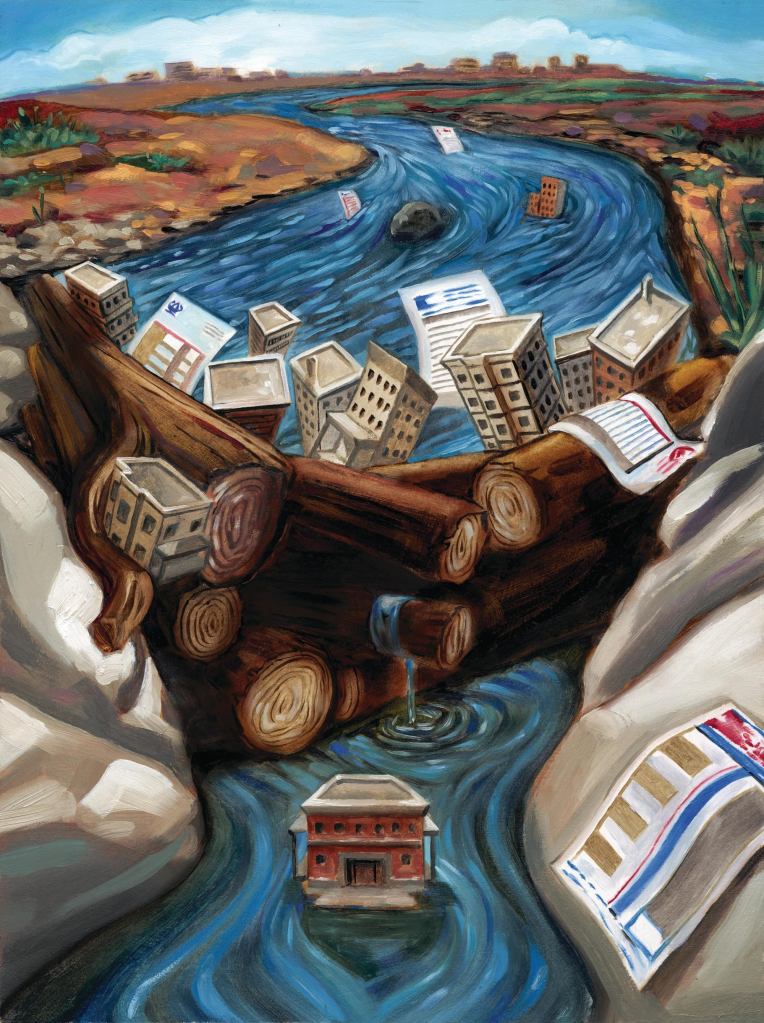

Thypin and his colleagues at RCA have speculated that the trend has resulted in what they call a two-tiered market—one where there’s a vibrant exchange of assets in top-tier markets such as New York and D.C., and a second tier in depressed markets where trades aren’t happening because assets are stuck in special servicing. The assets with servicers aren’t on the market. “The capital that would be chasing these assets if they were available is now going after these Class A properties,” he says. “The inventory is there. It’s a question of whether it will ever come out in a real way.” Lynd is concerned that if a flood of CMBS deals do come to the market at once, it could suddenly cause values to plummet by throwing the supply/demand equation out of whack.

But others don’t see a flood of distressed properties hitting the market and depleting values. “In the markets that [special servicers] think will take longer to come back, they’ll unload some of this soon,” says Christy Freeland, former chairman of Dallas-based Riverstone Residential, the second-largest property manager in the country. “They don’t want to let too many properties on the market at the same time to ruin whatever possible value that they have. If this year is any indication, maybe there will be a soft landing. Transactions have picked up somewhat and values have held steady and even gone up.”

Berger concedes on that point. “In general, the market has improved and there is more transaction activity,” he says. “In our portfolio in particular, we’ve definitely seen a big uptick in resolution and liquidation activity. A number of the assets have just worked themselves in a position where we can resolve them either by doing something with the borrower or taking back the property and selling it.”

And in some cases, servicers are actually seeing a decrease in the number of properties coming in. “We had been pretty steady through the end of last year. It had been on an incline,” Carp says. “But it slowed down a little bit in the last couple of months.”

Still, over the next few years, things could pick back up again (especially if the economy shows signs of falling into a double-dip recession). New York-based Fitch Ratings says the multifamily delinquency rate rose 17 basis points to 8.14 percent in June. Fitch expects that number to rise as high as 13 percent with the delinquency of the Peter Cooper Village/Stuyvesant Town loan. “You start to see maturities ramping up in 2011, 2012, and 2013,” adds Peter Donovan, senior managing director of Los Angeles-based CB Richard Ellis’ Multi-Housing Group.

And if that means more assets do end up in special servicing, it’s little doubt apartment owners across the country will be on the edge of their seats to see how Farkas and the rest of his colleagues react.