Playing the Field

As the distressed landscape changes in coming years, more buyers—including the well-capitalized REITs—will be racing to close on the right deals.

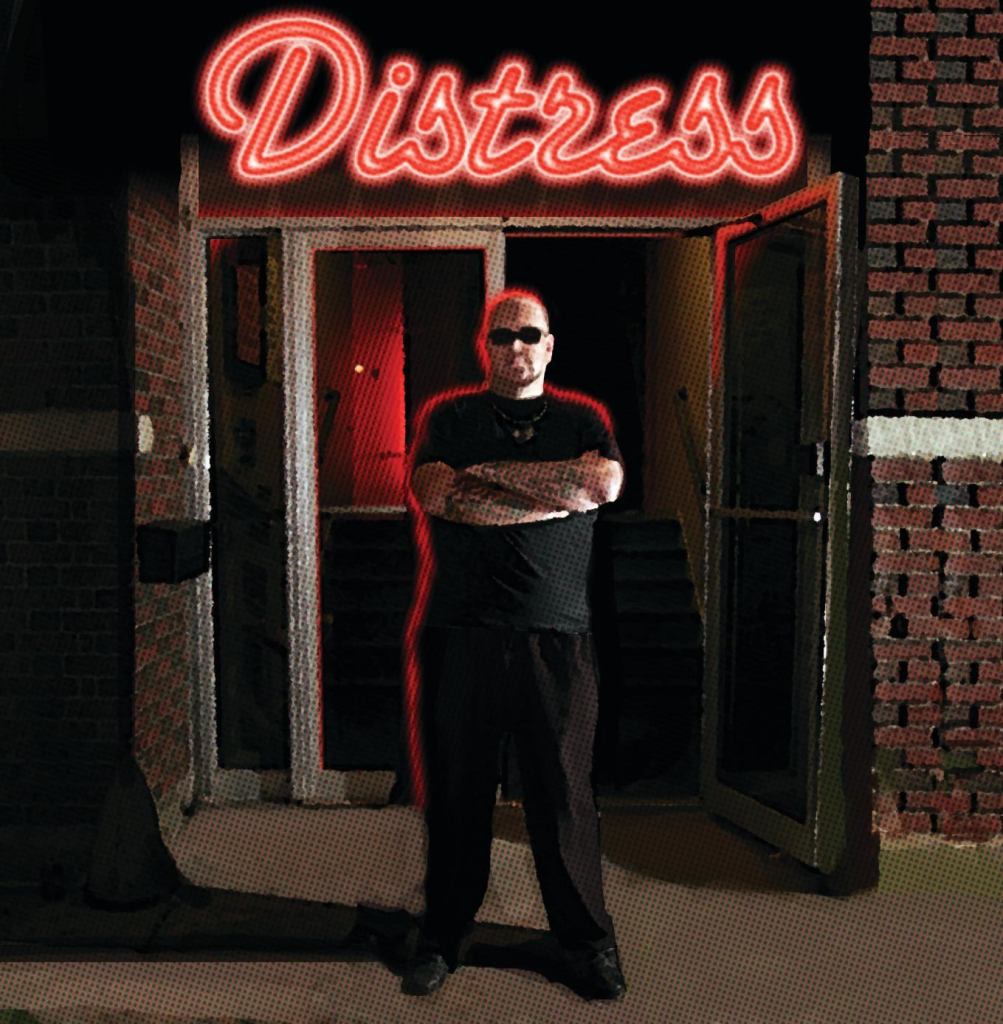

Bill Shippen has done a lot of distressed deals in his career—and this cycle is no different. While he’s characterized the current sales environment as “vapor lock,” the principal of the Atlanta office of Chicago-based brokerage firm Apartment Realty Advisors (ARA) has completed five sales (roughly 600 units) and talked with countless bidders since the beginning of 2009. And things are starting to pick up.

“We are getting tons of offers on properties,” Shippen says. “We’re getting twice as many offers on properties that we’re listing than we got two years ago. We feel like there’s more equity chasing those deals than there has been in this cycle.”

And things could get even crazier if more distressed assets shake loose. “I think the competition will be intense once things start hitting the street,” says Robert E. Hart, CEO and president of KW Multifamily Management Group, a Beverly Hills, Calif.-based apartment owner with 10,000 units in the U.S. “There will be a few players to take it down. There’s a huge desire on the sidelines to get stuff.”

The people looking for these quality deals come in all shapes and sizes. But as more properties become distressed over the next few years, the composition of those buyers could change. And, if some of the early pioneers reap rewards with their purchases, they can expect a lot more competition as more distressed apartments hit the market.

The Current Bidders

If you have been selling apartment properties during the past five years, you may not recognize the people bidding on assets today. On distressed deals, Shippen says only about 50 percent of the current bidders were active in the last real estate cycle. The other half either hasn’t been bidding for deals in awhile or has stuck with retail and office investments.

“It’s a lot of new people. A lot of those people were players back in the early ’90s,” Shippen says. “They’re coming back in. They bought in 1992 to 1995, hung out, sold in 2001 and 2004, and have been sitting on the sidelines. Now they’re ready to do it again.”

The other new faces that Shippen sees come from the remaining commercial real estate sectors. They actually see more potential in multifamily distress than the battered retail and hospitality markets. “We’re seeing folks who have raised money for the office sector beginning to look at multifamily because they can get 65 percent to 70 percent financed,” says Al Pace, president and CEO of Pacific Property Co., a Palo Alto, Calif.-based apartment owner that’s purchased 16,770 apartment units since 1999. “You will see these distressed players move into multifamily because it has cash flow.”

In addition to being new to the multifamily sector, these groups also share a common thread—they’re private. “I think that there are a lot of private funds out there; it seems that everybody has got a joint venture these days,” says Eric Bolton, CEO of Mid-America Apartment Communities, a Memphis, Tenn.-based REIT with 42,252 units.

The reason for the private interest is easier to understand. High-net worth individuals don’t have to get an investment board to sign on their deals. They can take chances pursuing risky distressed deals. “Private capital and high-net worth individuals are the most active,” says Joe Leon, a partner at Hendricks & Partners, a broker based in Phoenix. “Family trusts and high-net worth buyers are nimble and can be more aggressive. That’s a big issue with a bank or a seller that’s motivated to get a transaction closed.”

The smaller, private buyers also have significant local market knowledge, which can make them more comfortable. “The buyers have typically been someone who is local, and they know what’s viable and what’s not,” says Dale Conder, COO and chief risk officer with A10 Capital, a lender based in Boise, Idaho.

These buyers may also be content with lower-grade deals in tougher neighborhoods, which is a lot of what’s coming on the market right now. “Every city has buyers that will buy more challenged deals with all cash,” says Mike Kelly, president and co-founder of Greenwood Village, Colo.-based Caldera Asset Management, a turnaround management and restructuring consulting company specializing in multifamily loans. “They know they can manage this rough clientele for x per door. That will be a local guy who has local management [expertise] and is not afraid of the submarket and economic risk.”

Competition on the Way

While the private buyers are often the first to bid on distress assets, many people predict they won’t be alone for much longer. “Generally, the private buyers are the first to buy and sell,” says Lili F. Dunn, senior vice president of investments at AvalonBay Communities, a REIT with 50,114 units based in Alexandria, Va. “They also represent the majority of the buyers. They usually have more of a tolerance for risk. They may be the first to buy and the first to sell. Until recently, most of the buyers have been small, private buyers or regional companies.”

Pat Barber, president and CEO of Encore Enterprises, a Dallas-based commercial real estate firm with 436 units, knows the institutions will eventually be players in the distressed (or, at least, discounted) space. That’s why he’s trying to make his move now.

“In the early stages, there’s always a lot of private money,” Barber says. “Then the institutional capital will come in when there’s a lot of money transacted on the private side.” [For more on Barber’s strategy, see “Barber’s Shop” at right.]

Dunn already sees this trend taking place, even if it’s not in the purely distressed space. “Now, many investors seem to be taking an entrepreneurial approach. Some were outside of real estate, such as foreign buyers looking for relatively stable investments,” she says. “Recently, we’ve seen REITs and other traditional buyers re-emerge into the market.”

So far, AvalonBay and Mid-America are among the few REITs to actually close deals this year. Avalon isn’t specifically looking for distress, but for value-added deals where it can improve fundamentals and NOI. Regardless, the consensus seems to be that these large firms will eventually get their pick of deals.

“I think the REITs will have advantages because they have better access to capital,” says Paula Poskon, a senior research analyst with Milwaukee-based wealth management and private equity firm Robert W. Baird. “If Mid-America decides to buy something in San Antonio, they have enough flexibility to go in with an all-cash offer, buy something, and refinance it later. If they came across a portfolio, they could do an equity offering, and it would be very well-received. Any REIT that thought they had a growth opportunity could tap into the public markets and it would be well-received.”

Others think REITs could be focused on bigger moves than just buying one-off deals. “We could see the acquisition of entire companies,” says Nicholas Michael Ingle, director of capital markets for Hendricks & Partners. “Developers get bought. There’s an opportunity for deal making, but people haven’t gotten their head around it yet. That’s where I would see the institutions get an upper hand on the private guys.”

But Ingle doesn’t expect all institutions to become suitors for distressed apartments or their notes. Right now, life companies and pension funds are more focused on selling. “They’re pretty scared and burnt from losing so much money over the past five years,” he says. — Les Shaver

Barber’s Shop

For a year, Pat Barber watched and learned. Now, he’s ready for a buying spree.

Pat Barber, president and CEO of Encore Enterprises, a Dallas-based real estate firm with 436 units, has been busy the past year. He’s looked at $2.2 billion worth of Class A property in various commercial sectors, about 25 percent of which was multifamily. In February, he plans to close his first deal—a 504-unit, 452,000-square-foot project in Dallas. Some people might think that’s a low success rate. But Barber says that’s all part of his plan.

“We wanted to watch before we started striking to make sure we wouldn’t leave money on the table,” Barber says. “During the first six months, we were monitoring, underwriting, and bidding. We wanted to find where the strike would be. We’ve used this year to get ourselves positioned. We were willing and ready to buy the asset but weren’t ready to stretch.”

Now, he wants to get serious. “We started recalibrating and then started making the final call for offers,” he says. “A few months ago, that’s when we decided it was a good time, and we needed to move in and become very active.”

So far, he’s bought two properties, including a 500-unit apartment in Dallas and a retail property in Cincinnati. He wants to buy more because he’s afraid institutional buyers will become active and begin muscling smaller players out of the market. “That’s why we’re transacting now,” he says. “We think that institutions will come in and change the market.”

Barber has also learned to be cognizant of what sellers want. In a distressed situation, they’d often like to off-load the asset as soon as possible, so they’d like earnest money up front and certainty of closing.

“We realized in getting these deals done that certainty of close goes a long way,” Barber says. “People are choosing us for the certainty. We’re willing to put significant dollars in to go hard quickly, close quickly, and give sellers confidence. We’ve found that this is a good way to obtain contracts on properties that fit within the criteria of what we would be looking for.” — Les Shaver