But do they really? While statistical analysis of green versus traditional buildings are now becoming available in the single-family, master-planned, and commercial/office sectors, there’s an acknowledged lack of empirical heft on the multifamily side of the fence. A March survey of Energy Star-rated commercial office buildings by the Royal Institution of Charted Surveyors (RICS), for example, found that buildings with a higher Energy Star rating commanded effective rent premiums of more than 6 percent per square foot compared with nongreen buildings of the same size, location, and function. The study further determined that Energy Star buildings realized a 16 percent premium on the disposition market.

Search all you want, but you won’t find similar studies analyzing multifamily green savings, likely a result of too few green multifamily projects in the landscape now. When it comes to determining greater disposition gains for green in multifamily, “we’re just not there yet,” says Doug Walker, senior vice president of asset quality and green initiatives for the Denver-based REIT UDR. In addition to a relatively small percentage of existing multifamily housing stock qualifying as green from a certification standpoint, the total lack of deal flow in the industry makes such a comparison impossible in the current operating environment. “When we get back into buying and selling mode—and have been able to track lower operating costs for these green buildings—over time, from a value standpoint, I think it would be hard not to generate some additional gains.”

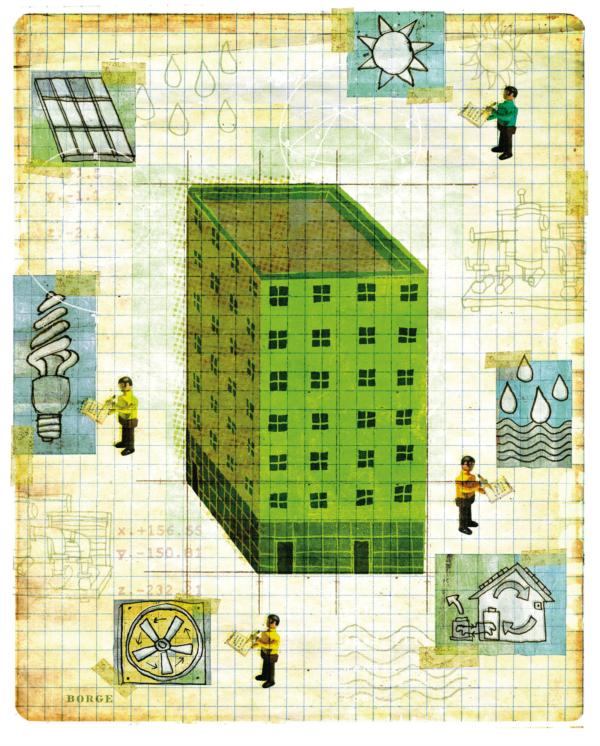

Walker—and UDR—are banking on that. The company has spent approximately $250,000 across its 44,571-unit portfolio installing compact fluorescent light bulbs and programmable thermostats. This month, UDR will begin a year-long test of its occupied apartments, comparing those that have seen various levels of green retrofitting (some have received lighting or HVAC upgrades; others have had Energy Star appliances installed) against a control group of apartments. The goal is to allow UDR to “measure consumption with the same type of units in the same type of exposure,” Walker says. “We want to know exactly what the differences are, what impact the changes have independently. We should be able to share that information and provide real, live multifamily data that, to our knowledge, no one has produced.” Walker says that until multifamily players can quantify the precise savings of green versus nongreen, it will be difficult to determine accurate premiums when it comes to disposition.

On the property management side, multifamily Internet listing service Apartments.com annually queries a database of some 500,000 renters nationwide to determine their green preferences and practices. According to survey results released in March, 60 percent of renters said they search for apartments that offer environmentally-friendly amenities such as recycling programs, energy-efficient light bulbs, low-flow water devices, and paperless transactions. Twenty-five percent—a sizeable number, but still only one out of four renters—say that they would pay a rent premium to live at a green apartment community, although they were not asked to quantify the premium. That premium-minded percentage of renters has not changed since 2007.

Judi Schweitzer, president of Irvine, Calif.-based sustainable development consultant Schweitzer + Associates, has conducted similar research with comparable results for private clients in the multifamily space and says she’s been surprised to see those clients breeze over the data. “I don’t know if multifamily doesn’t believe what these surveys are saying or what, but there is clearly a huge pent-up demand among renters for green apartments,” Schweitzer says. “It’s likely the split incentive dilemma—a disconnect between the investor and the beneficiary and/or a disconnect between the investment and the return on the investment at widely differing points in time.”

Proving Out

That disconnect can occur more than once across the multifamily life cycle, as well. Solar energy, for example, could be an investment made by a multifamily builder that’s not realized in a disposition, provides little or no return on investment to successive owners of the real estate, and only benefits property operators and residents after the cost of the technology has been amortized over a 20-year hold. [See “Hot Stuff,” below.] “You’ll probably have to quantify some of the cost savings of green in your rearview mirror, that’s true,” Schweitzer says, “but remember some of the benefits are certainly qualitative as well, and finding that balance of economic costs and environmental and social benefits is the art of sustainability.”

Perhaps optimistically, it’s among the builder set where green—and particularly the use of LEED and other certification programs—seems to be gaining the greatest traction, despite the lack of a complete philosophical buy-in to sustainability dogma. This is likely the result of their wanting to leverage existing programs and financial incentives, politics aside. “I don’t need a score, and I don’t need a piece of paper that says I am a platinum or gold or green or tin,” Walker says. “If the main focus is to become greener and more aware of the sustainability of our product, that’s where we should be headed.” Like a growing number of developers, Walker nonetheless supports rating systems for three reasons: the programs demand collaboration among stakeholders that lead to a better quality product; they result in easily quantifiable savings to energy expenditure line items; and doing something—anything—is better than doing nothing at all.

“When you can get behind something like green building, it provides a force that motivates people to come together on a project even more,” attests Jeff Bunker, president of San Diego-based multifamily builder Wermers Cos., which just completed construction of a 42-unit affordable apartment community for Wakeland Housing that is expected to get LEED Platinum certification. “Regardless of what type of certification it is, the more projects that get built and the more architects and developers who get experience going green, we can begin to determine where we’re getting real benefits versus the bullet points that just sound good on paper.”