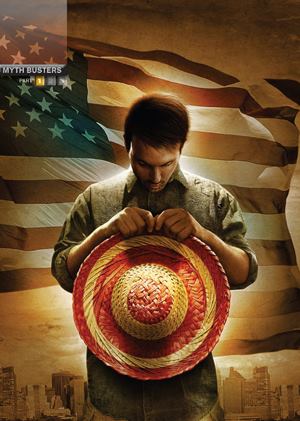

Myth 3

Requiring documents won’t affect operations, values.

Unfortunately, deciding to what extent you will pursue documentation may no longer be optional. Local governments in smaller cities such as Hazelton, Penn., and Farmers Branch, Texas, have crafted legislation that is aimed at keeping illegal immigrants out of their towns by fining the people who rent to them. But federal judges shot down these attempts to curb illegal immigration. In Escondido, Calif., for example, proponents of an anti-immigration law eventually backed down—and California subsequently passed a law making it illegal for towns to ask for citizenship verification.

Indeed, states are active as well. State legislatures considered 85 bills in the first quarter of this year that would create stricter guidelines with regard to proof of residential status in obtaining an ID, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. All in all, in 2007, 1,562 bills related to illegal immigration were introduced nationwide, and 240 were enacted, three times the number that passed in 2006, according to the organization.

“Those types of ordinances have largely been put on hold pending lawsuits and federal action in Congress,” NMHC’s Befus says. “The state and local ordinances have particularly targeted apartment owners and, if implemented and enforced, would be quite burdensome and totally inappropriate.”

What’s more, there’s no requirement under federal law for apartment owners to check that much information, says David Crump, director of legal research for the Washington, D.C.-based National Association of Home Builders.

As a result, each time one of these towns passes a law, outrage from the apartment industry usually follows. It’s no wonder when you consider the fees and penalties associated with the laws had they gone into effect. Hazelton attempted to fine landlords $1,000 per day for each day a landlord rented to an illegal alien. In Farmers Branch, the fine was $500 a day. “Local governments enact policies where local businesses have to be the police,” says Campo of Camden. “It’s unfair for the business. They are not really prepared to deal with it.”

Training property managers to conduct these checks or hiring a third-party verification firm would be an additional cost for apartment owners. Plus, most site-level staffs—a mix of high school graduates and students fresh out of college who know little about real estate or legal liability issues—can’t conduct proper background checks. “There’s no way we can expect a property manager to be qualified to play border agent,” says Akins of the Bascom Group.

The added effort of doing background checks isn’t the only reason apartment owners want to avoid towns that require verification. Vela says that in Cobb County, Ga., where the county put forth legislation in 2007 to limit day laborers and overcrowding in apartments, occupancy rates fell from 80 percent or 90 percent to the 60 percentiles. “I don’t know about long-term property values, but I can tell you from a daily and NOI [net operating income] perspective, it hits your bottom line,” he says.

And once such legislation turns up—whether enacted or not—even legal immigrants flee the area. “It sends a message to the immigrant community. They get the message, and they leave,” Bowdler says.

These falling fundamentals mean that apartment executives such as Starpoint’s Budman are wary about buying in cities with activist governments. “With people buying more on cash flow than appreciation, I think that occupancy has a direct effect on value,” Budman says.

Akins doesn’t own units in Farmers Branch, where they have attempted to supply citizens with a special card (landlords would be able to rent only to people with this card), but he does have properties in nearby Addison, Texas, which is more open to immigration. “If I am looking at an apartment, I’m not going to the city to register,” Akins says. “I will just go to Addison.”

Even beyond cash flow, liability, and the possibility of extra overhead, Vela, who is Hispanic, believes there is an ethical responsibility for apartment owners to avoid these cities. “My company won’t go into a governmental situation that is against any group of people,” Vela says. “We’re not going to spend our money in your community if you don’t support all people. I know we’re not alone on that.”