Reducing the clearances in all public circulation space. This is the load factor pitfall. For example, the idea of cutting a corridor width down in a long building can prove to be irresistible. One little inch times many feet times many floors adds up in the most enticing way. As stair and lobby areas are cranked tighter, the number in the little box down in the lower right corner of the spreadsheet grows and grows. “What savings. No one will even miss it.”

Wrong. In this case, losses are hidden away in the future, which begin to reveal themselves when the first customer rounds the corner to have a look at a new lifestyle. That $20,000 first impression made in the furnished model unit has just been undermined as a customer approaches a long uncomfortably narrow corridor or an overly tight building entrance. Are the saved inches really worth the lost value of slow sales?

Cut back on public amenity space. More of the same as the previous pitfall, cut a bit here and cut a bit there, and maybe a whole studio can be added by getting rid of that little meeting space. Whether you’re planning to own the building or sell it, keeping the right amount of amenity space in the design is a must. This time, less is not more. In fact, having too little public space can cost months of interest while waiting to sell or rent up.

Decrease service space. There are many kinds of service space in a building – storage, mechanical and electrical, resident storage, maintenance, the list goes on. However, very little money is actually saved when an unfinished, unheated space is trimmed. Lots of money will fly out the window during construction, however, when a subcontractor runs out of space for code clearance in front of an electrical panel or a 6-inch sprinkler riser won’t quite fit where it was planned. Be sure that service spaces really work for the intended purpose prior to trimming. The message again is to think before cutting, which quite possibly, may prevent a pain in the wallet down the road.

How Much Can Be Saved? All multifamily projects are handled differently. Everyone has trade secrets for saving money, holding a competitive edge, and capturing marketshare. In this light, all business modalities fall somewhere in an organizational spectrum ranging from design build on the private sector side to full bid on the public sector end. But no matter where a business falls on this line, it wants to save money and be able to quantify the savings.

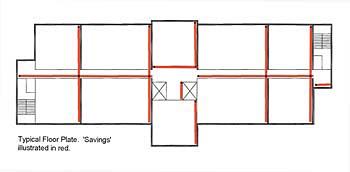

For this to happen, a base line has to be established, which is usually predicated in some fashion on raw square foot costs, and here is where the fallacy begins. It appears that savings can be attained and targets met by holding the line on size and squeezing things down. However, dollar savings from squeezing rarely include reduced heating ventilation and air-conditioning, plumbing, fire protection, or electrical costs. What savings are left fall into the raw structure and finish categories and amount to only a fraction of overall square footage costs.

One could argue that square foot pricing and cost per unit comparisons, while useful as tools during the early reckoning stages of a project, become increasingly meaningless as the nickels and dimes on the spread sheet give way to the vicissitudes of construction and open house parties. In fact, it’s as difficult to account precisely for these kinds of hidden cost savings and value-added tactics as it is to bank on anticipated revenue from curb appeal.

Curb appeal is never seen as a line item, but does add real value to a project. Look hard at both the successful and not-so-successful projects of the past. What were the real root causes for the successes and failures?

The Message The suggestion here for the more fastidious bean counters is simply this: Stop holding the line so blindly. Take a fresh look at the construction side instead of just the spreadsheet when deciding how to make it all work. Know the difference between real savings and perceived savings. Most importantly, have faith that a smart and well considered design will prevent the losses, headaches, and stresses that accompany an overly tight design.

– Robert H. Kleven, AIA, is an architect with Wimberly Allison Tong & Goo and is based in its Seattle office. Previously, he was with the Johnson Braund Design Group Inc.