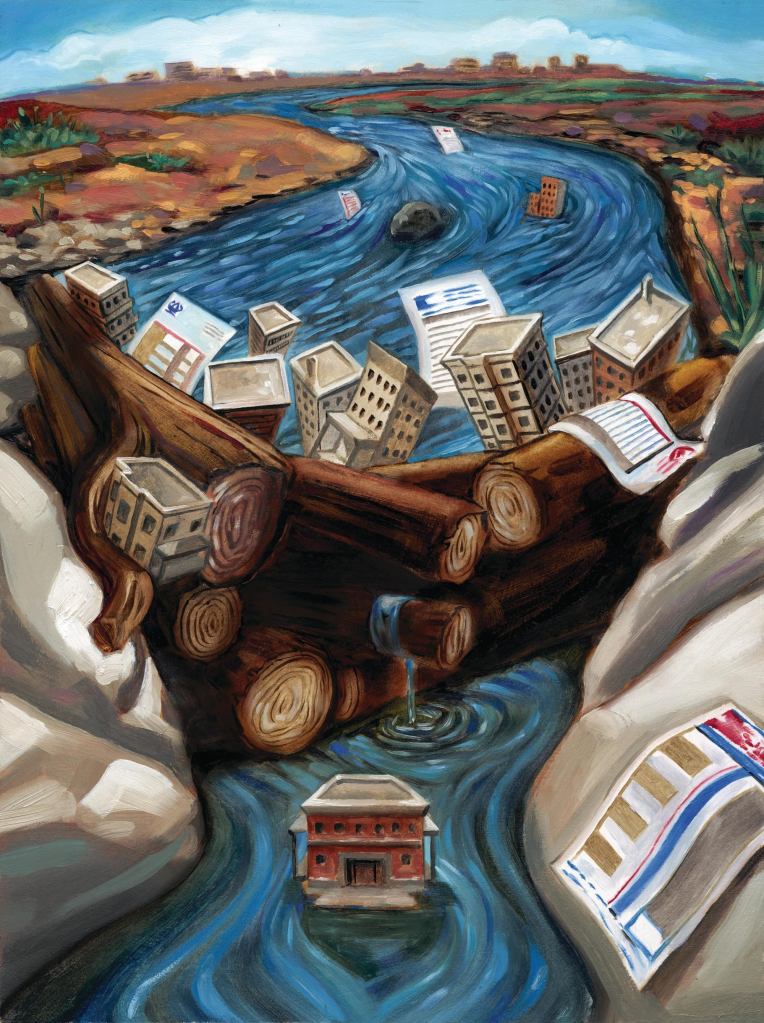

In fact, over the past 18 months, special servicers have gobbled up multifamily assets across the country. As of June, $17.8 billion worth of assets, totaling 1,542 properties, have ended up with special servicers. That’s up from $1.7 billion in assets, or 290 properties, which were with servicers in December 2007; and $4 billion in assets, totaling 537 properties, which were with servicers in December 2008.

Multifamily owners and managers see these billions of dollars of assets sitting with special servicers and many of them aren’t happy. Frustrated by the lack of buying opportunities, they wonder if something more sinister isn’t at play, or if conflicts of interest like those raised by Farkas and other special servicer buyers aren’t to blame for the length of time—averaging approximately 15 months (according to Trepp)—that special servicers are keeping these assets on their books.

But many servicers say that multifamily owners simply don’t understand the CMBS process. They assert that they’re simply doing their jobs and focusing on maximizing returns for their investors. And the overwhelming volume of the assets, and the delays caused by that, have apartment owners discouraged. Basically, servicers believe apartment owners are making them the scapegoats.

“What’s in the marketplace today is a general level of frustration, which is manifesting by certain people implying bad motives on behalf of some parties,” says Spencer Levy, head of the restructuring and recovery service team at New York-based CB Richard Ellis. Who’s right? It depends on which servicers you’re talking about. But what isn’t in dispute is that a glut of properties are reaching servicers, and that could have wide-ranging implications down the road.

Borrowers at a Disadvantage

In the mid-2000s, well before Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac shouldered the burden of apartment financing, CMBS offered great pricing for buyers. Borrowers would get 90 percent acquisition or refi leverage, while the GSEs were limited to no more than 80 percent. And most importantly, CMBS loans were almost always nonrecourse, versus many banks that required personal guarantees.

| Transfer Time | ||

| Although the length of time to transfer to special servicing hasn’t greatly increased, the number of loans moving through that pipeline has skyrocketed. | ||

| Year | Disposal Time (In Months)* | Loan Count |

| 2004 | 15 | 48 |

| 2005 | 16 | 68 |

| 2006 | 17 | 44 |

| 2007 | 16 | 68 |

| 2008 | 11 | 70 |

| 2009 | 14 | 141 |

| 2010** | 15 | 117 |

| Average/Total | 15 | 556 |

| * No. of months between transfer to special servicing and loan disposal | ||

| ** Through May | ||

| Source: Trepp | ||

“It was cheap money,” says Brock Andrus, a senior director at Dallas-based 1st Service Solutions, a borrower advocacy firm specializing in loan restructuring and assumptions. “The underwriting guidelines were free-flowing. People stood in line to get this type of money.” But there was a catch—borrowers didn’t exactly know where their loans were going. In that way, they were akin to the typical subprime-borrowing consumer profiled in the news. “They had no idea how that process works,” says Ben Thypin, senior market analyst for New York-based research firm Real Capital Analytics (RCA). “They got a loan, liked the terms, and sent payments to whatever address they were given. Now, people realize it matters who your lender is.”