Indeed. As more and more loans run into trouble and get passed to special servicing, owners are finding themselves facing significant amounts of bureaucracy.

For example, the special servicer has to do a complete evaluation of the loan file, review the original underwriting, conduct a site inspection, and order an appraisal. Then, it meets the borrower and writes a business plan that must get approved through internal committees and controlling class approvals. Depending on the jurisdiction, a special servicer or court can appoint a receiver to take care of the asset in the meantime, including finding a property manager.

“In a typical default scenario, it takes a good 12 months to get a resolution,” says Stacey Berger, executive vice president at Midland. “If you sell the REO, it will take 90 days to assemble information, hire a broker, list the property, go to market, accept offers, negotiate, and close.”

Often the servicer finds it best to remove the borrower altogether. “In a lot of troubled multifamily properties, the borrower is the problem,” Berger says. “In those cases, if the borrower is not part of the solution, our motivation is to get rid of the borrower and exercise our rights to take control of the property.”

But some owners contend that servicers may be slightly too aggressive in pulling in assets. “If you’re a borrower and have CMBS stuff coming up, I’m seeing servicers foreclose immediately,” says one multifamily manager with units throughout the Midwest, Southeast, and Southwest, who asked to not be identified for this story. “Unless the borrower is coming to the table with cash to pay down the note, there’s not even a discussion to be had.”

In fact, there’s a train of thought out there that servicers are being aggressive, prematurely pulling assets into servicing. “There are a lot of properties put into special servicing in order to facilitate restructuring discussions,” Thypin says. “That’s created additional work for them.”

Berkadia’s Carp adds that, in fact, a willing borrower can go a long way towards speeding up the servicing process. Still, these borrower/servicer tugs of war only add to the backlog already in place.

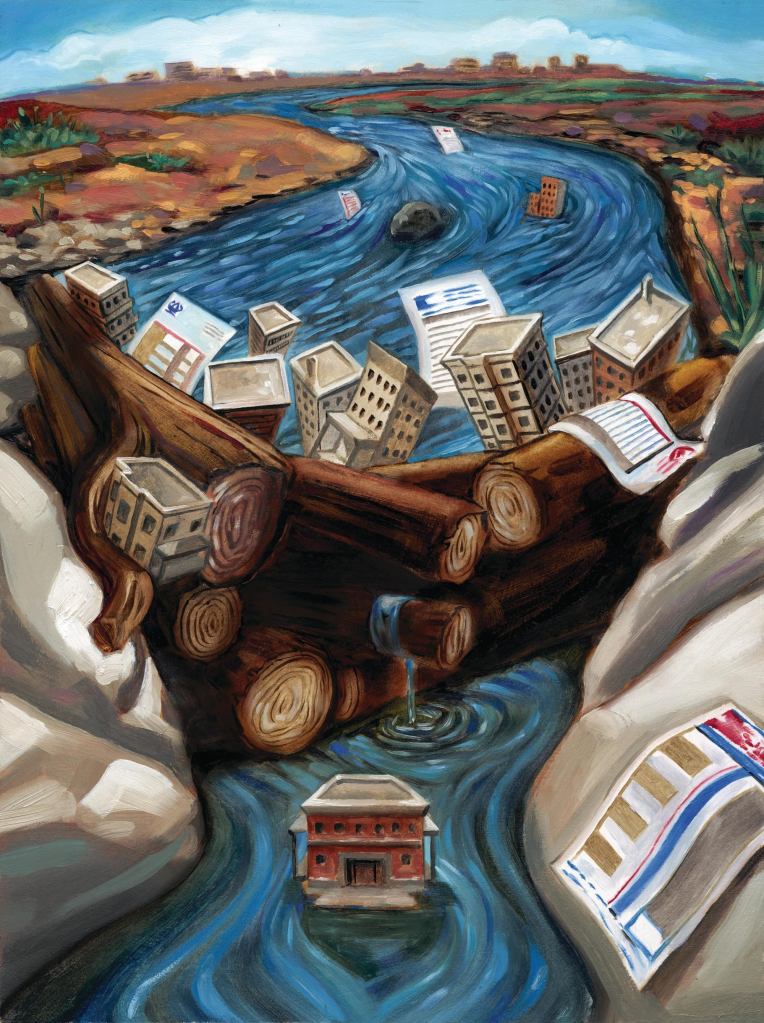

The Logjam

Flash backward—to a time before borrowers and servicers played this elaborate, high-stakes game of chicken. Back before rents collapsed (and then, perhaps, started to rise again). Back when unemployment hovering around 4.5 percent was considered unreasonably high. Think 2006. That’s about the time that Berger says Midland recognized there would be an influx of distressed properties coming into the special servicing pipeline.

At the end of 2007—after Bear Stearns fell and cracks in the economy began to appear—Midland had 18 asset managers. Now it has 49. And it needs them. “We continue to see a significant inflow of assets come into special servicing,” Berger says. “The pace of transfers accelerated dramatically in the fourth quarter of 2008 and has continued unabated.” Berkadia says that when it operated as Capmark, it had excess property managers in 2006 and 2007 working in CDOs and Low-Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC). As it needed them in special servicing, it moved them over. But talk to other people in the industry, and they think the Midland and Berkadia stories may not be the norm. They say this volume was “unforeseen” by servicers. “It takes a lot of capacity on the servicing side to handle the deal flow,” Andrus says. “Some of them are catching up, and some of them aren’t. They don’t have capacity to get into deals to understand each asset and submarket and the buildings surrounding those assets. There’s just an overwhelming amount of deals.”

And, in fact, these mobilizations still may not be enough. A representative with one brokerage firm who preferred to remain anonymous called the process glacially slow. “A couple of years ago, when we talked to special servicing groups, you had a handful of asset managers,” he said. “Since then, they’ve gone on hiring sprees, and they’re still buried.”

Which helps explain why some assets can take as long as 18 months to work out. Usually, those workouts and resolutions mean one of three things: Either the loan is sold; the servicer will write down the loan to today’s value and let the borrower stay in; or the servicer may decide to sell the asset outright.

Unfortunately, in some cases, borrowers are not interested in the assets that hit the market. And the assets owners want access to don’t seem to be available—whether they’re delayed in special servicing or being held onto by the servicer. “This massive buying opportunity that we all thought we were going to see from CMBS hasn’t materialized,” says the owner with units throughout the Midwest, Southeast, and Southwest, who preferred to remain anonymous. “They’re holding their cards to the vest. You can’t buy from [the servicers]. They’re not listing stuff to sell it.”