And there’s really nothing forcing their hand, either. CMBS loans can be extended, and there’s no mechanism to require CMBS write-downs. “In the banking world, regulators come in and say, ‘I don’t believe the value is there. Write it down and clean it up,’” Andrus says. “There’s no hand like that for special servicers. They can take their time to work through this.”

But Carp scoffs at this. He contends that there’s really no reason for servicers to be long-term owners. “We’re not great owners because a lot of the owners can do more on the repositioning and cap ex than we can do,” he says. “They can do it cheaper than we can. We price it to sell it.”

Ultierior Motives?

Despite what Carp says, there are still skeptics out there wondering if there aren’t other motivations at play. Mainly, these skeptics are apartment brokers and owners. Their contention: There are other reasons that servicers are getting backlogged with assets, and it’s not just because the process takes a long time or that volume is growing.

“Their incentive to work these issues out is not really there,” says the multifamily manager with units throughout the Midwest, Southeast, and Southwest, who only spoke anonymously. “I think there’s some inherent conflict between their willingness and desire to sell them.”

Under this theory, servicers have a large backlog of assets and want to keep these properties on the books for self-preservation. “Big companies have been built with thousands of employees servicing these loans on behalf of investors and lenders,” says one apartment owner based in the Southeast, who also spoke on the condition of anonymity. “If they get 1 percent a year to manage it, why would they stop? They will manage that for 20 years and build a company around [the fee business].”

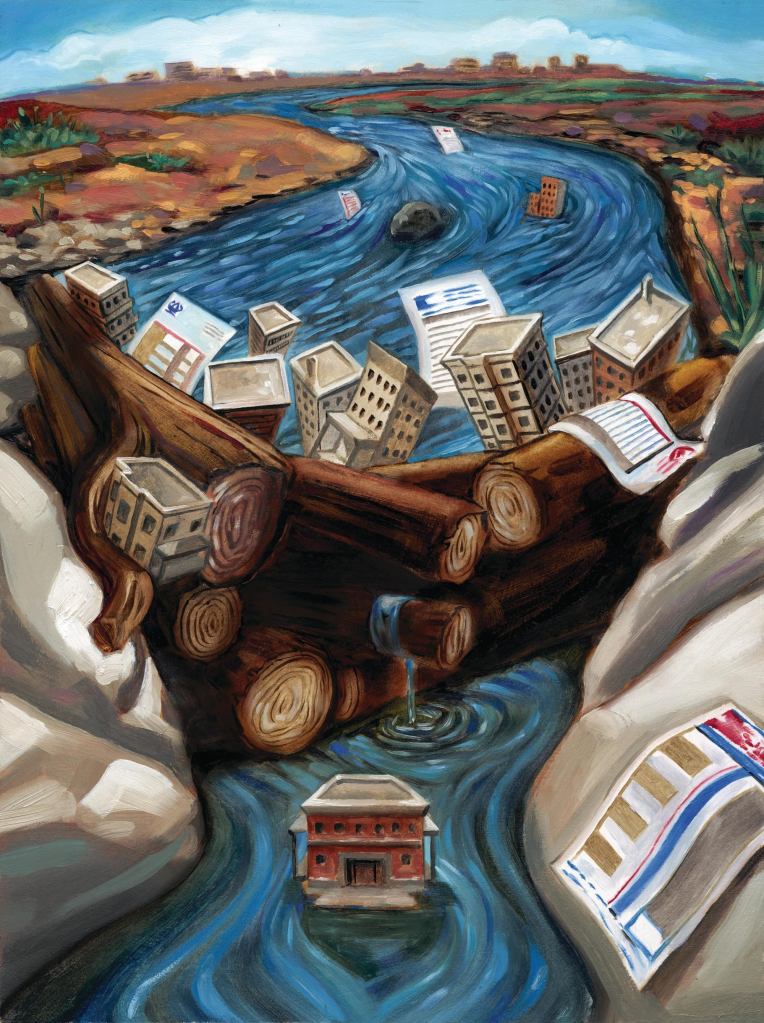

The Path to Special Servicing

Here’s how a CMBS asset ends up in special servicing.

STAGE 1: A Loan is Born

A borrower works with an originator to sign a CMBS loan for a single asset. In the height of the market, this was because CMBS loans often offered better terms than their competitors. That originator repackages the loan and sells it to different customers, such as insurance companies and pension fund managers.

STAGE 2: Structure is Established

First, a primary servicer steps in with responsibility for direct contact with the borrower and to begin collecting and remitting payments. Then, a master servicer (usually the same company that handles primary servicing) assumes the role of overseeing the primary servicer; remits payments to trustee; does investor reporting across portfolios; advances principal expenses; and handles approvals or requests from borrower or assignment of assumption or release of reserve.

STAGE 3: Running Into Trouble

If a loan hits bumps—often a delinquency of 60 or more days, a default by the borrower, or an imminent judgment—it’s up to the master servicer to pass the loan to a special servicer. If the loan starts performing again, it can be transferred back to the borrower. If not, the special servicer begins the foreclosure process, which can take as long as a year.

STAGE 4: Borrowers Ask for Help

If a borrower can no longer make payments, he can ask for transfer to special servicing in order to try to modify loan documents. Borrowers usually want loan modification with a lower rate, but lenders often aren’t playing along. As a result, if the transfer request is considered, the master servicer will collect information about the borrower’s business, operations, and market data.

Mark Johnson, vice president of multifamily investment sales of the Multifamily Advisory Group at Colliers International, a Seattle-based commercial real estate services firm, notices that servicers are making a real effort to move CMBS deals priced less than $5 million, while trying to keep sponsors intact for deals valued at more than $20 million. Why? Johnson suspects it’s because they don’t want to take losses. “They’ll take a $400,000 hit to get rid of a fee product that’s small and management-intensive,” he says.

But some servicers argue that resolution brings more money than continuous management. “The profit in our special servicing is through resolving assets,” says Berger of Midland. “That’s what we get paid for. We have a significant economic incentive to resolve assets.”

Carp seconds this. “The big money is in liquidation fees,” he says.

The problem with that assumption is that not all servicers make the same types of management fees. Those fees vary by servicer (as do the property management fees), and are based on the confidential Pooling and Servicing documents. This mystery clouds the situation even further. “It’s hard to pin down what servicers can do,” says RCA’s Thypin. “It’s in their interest to keep loans in servicing. They have a lot of power, but they’re the only ones who know how much power they have.”

If fees were the only reason special servicers were holding onto assets, that’s one thing. But it’s not the only reason speculated that they’re clinging to apartments. They say the servicers also have a personal stake that provides motivation to hold the asset until it gains more value. It works like this: In many cases, the servicer has the B piece, or the most subordinated bond. By getting that, they become the controlling class, which allows them to appoint themselves as servicer.

“The structure was set up to make sure that servicers had skin in the game and their interests were aligned with other bondholders, but no one thought of how that would work when things went bad,” Thypin says. “Let’s say you have a loan in trouble. It’s in the best interest of the servicer, as the subordinated bondholder, to prolong that loan and make the process to fix that loan as long as possible. [That way] the servicer keeps getting paid.”

Not only do the servicers keep getting paid, but they retain hope that their pieces could possibly one day retain their value. Being in the first loss position, many servicers have lost some or all of their investment. By holding on, they don’t have to take that loss, and they can hold out hope for better days ahead. “They believe that market conditions will improve and that, as financing becomes more available, assets will trade at higher prices,” says an executive at one special servicer, who spoke on the condition of anonymity.