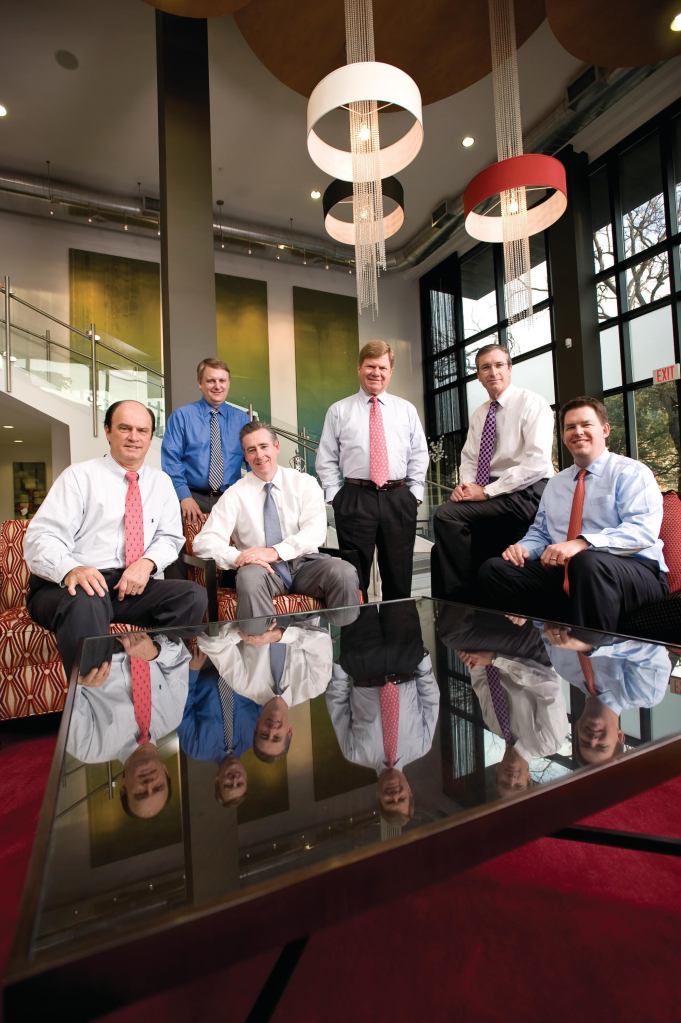

The bank eventually chose which deals they wanted to pursue, but Brindell doesn’t want them to make those calls in the future. He wants TCR’s investment committee of Brindell, Valach, Melaugh, Collins, MacDonald, and Dempsey to make those calls, together with the local partner. “We believe that in an environment of constrained capital, we must be more effective at allocating that capital where we believe it can generate the best risk-adjusted returns,” Brindell says.

The model partially comes from the public markets. “Like a REIT, we’re going to be a little more prudent in where we’re looking for opportunities and markets,” Valach says.

Still, will employees used to a high degree of autonomy bristle at a more structural approach? Brindell says the company will remain protective of its entrepreneurial heritage. Meanwhile, MacDonald and Collins say it hasn’t been a problem in their regions. “If we don’t upgrade, we run the risk at getting categorized as a regional developer that’s good at building things but that’s not capable of being a national company that can attract significant capital,” Dempsey says.

4) Emerge as the Best in Class.

From a shift to acquisitions to a desire for more efficient operations, Brindell’s changes have been made with one goal in mind—to attract more capital. In order to accomplish that, TCR needs to upgrade and standardize its reporting and accounting systems as well. Traditionally, the company could show equity and debt providers its success by the sheer number of units built, but Brindell says that’s an outdated metric.

“As a private developer, there were few metrics available to compare you against your peers,” Brindell says. “In the future, we’ll focus on quality rather than quantity, and we’ll seek to measure our performance against the best public companies in our industry.”

Quality development hasn’t been a problem, but most everyone believes TCR can make strides in reporting and systems. For instance, in the past, TCR managers in different regions may have treated net effective rents or concessions differently in their reporting. “I know a lot of the REITs can kind of look and see what same-store sales growth was a year ago property-byproperty by sitting behind a computer,” Valach says. “We can’t do that today, but it’s something that we need to do, if for no other reason than to be better asset managers and stewards of capital.”

Brindell’s changes could also open up other options for TCR. For instance, its system of financing individual deals via partnerships limits its financial flexibility. What with the capital market storms of the past couple of years, that lack of corporate debt has been a godsend, but it’s also hurt.

“It limited us from being able to present ourselves as an entity,” Terwilliger says. “About two years ago, we went through a series of discussions about potentially selling an interest, maybe even a controlling interest, in TCR. We had a very difficult time presenting ourselves as a company instead of as a series of partnerships.”

Whether it’s enabling TCR to sell an interest in the company or just open up a substantial line of credit, more consistent reporting provides flexibility. So if TCR wants to operate more like a REIT, be able to allocate capital more like a REIT, and make investment decisions more like a REIT, does the company that spun off Alexandria, Va.-based REIT AvalonBay Communities actually want to be a REIT? Brindell says no. “Nothing is ever excluded, but any kind of public offering is not on our list of priorities right now,” he says.